WHO labels Monkeypox a global public health emergency

On 27th September 2018 New Scientist magazine announced Monkeypox had reached the UK, with three people catching the smallpox-related virus in the UK for the first time. In mid May 2022 the magazine focused on the symptoms and how serious they are. In the same week they asked if it could become the next pandemic.

In late May New Scientist reported on cases increasing around the world. On 24th June they looked into how the global Monkeypox surge might be controlled. Now we’re in the midst of the biggest ever outbreak, the WHO has labelled it a global public health emergency, and they’re collaborating with the world’s health authorities to prevent it spreading any further.

Let’s take a look at the latest from Monkeypox, a virus that has made its way from Africa around the world in ways we still don’t understand.

Monkeypox has turned up in countries where it isn’t endemic

Early May this year saw cases of Monkeypox being reported even in nations where it isn’t endemic. Endemic nations were also reporting surges of the virus. Now we’re in the middle of the biggest ever outbreak.

Most confirmed cases that can be laid at the feet of international travel involve journeys to and from Europe and North America, rather than the virus’s usual West and Central African home. This is the first time the world has seen so many cases at once in non-endemic and endemic countries, and the sheer spread of the geographical area it has reached is unusual. So far Monkeypox cases have been reported in North and South America, Australia, Africa, the Middle East, parts of Asia and across Europe.

Most patients have been identified via sexual and other health services. Mainly – but not all the time – the cases are happening in men who have sex with men. WHO is ‘issuing guidance’ to help countries set up the right kind of surveillance, laboratory work, clinical care, infection prevention and control, risk communication and community engagement. They’re also collaborating closely with African nations, institutions, and commercial partners to prevent more cases.

How does Monkeypox affect health?

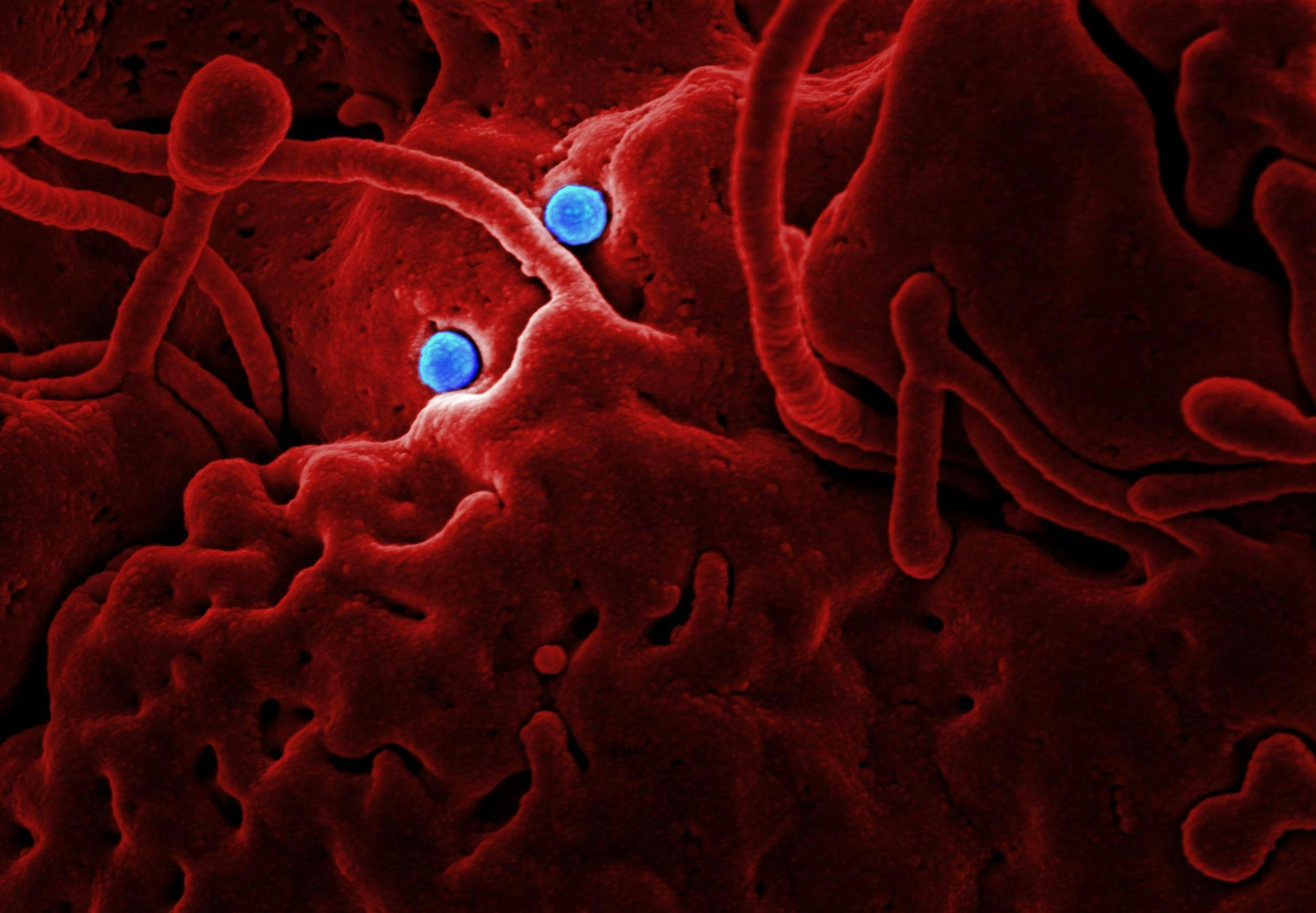

Monkeypox is usually mild. Most people get better without treatment, although it takes 14 to 21 days. Early symptoms might include fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills, and exhaustion. You might get a rash that looks like chickenpox, first on your face then spreading, often to the hands and feet. The rash develops into as few as one and as many as a thousand lumps and liquid-filled pustules which eventually form scabs before falling off. You remain infectious until the scabs have fallen off and you have a fresh new layer of skin underneath.

The WHO says the disease makes children more ill than adults. If you get infected when pregnant you can suffer from complications, including a risk of stillbirth. As they say on their website:

“In most cases, the symptoms of monkeypox go away on their own within a few weeks. However, in some people, an infection can lead to medical complications and even death. Newborn babies, children and people with underlying immune deficiencies may be at risk of more serious symptoms and death from monkeypox.

Complications from monkeypox include secondary skin infections, pneumonia, confusion, and eye problems. In the past, between 1% to 10% of people with monkeypox have died. It is important to note that death rates in different settings may differ due to a number of factors, such as access to health care. These figures may be an overestimate because surveillance for monkeypox has generally been limited in the past. In the newly affected countries where the current outbreak is taking place, there have been no deaths to date.”

Will Monkeypox become more dangerous?

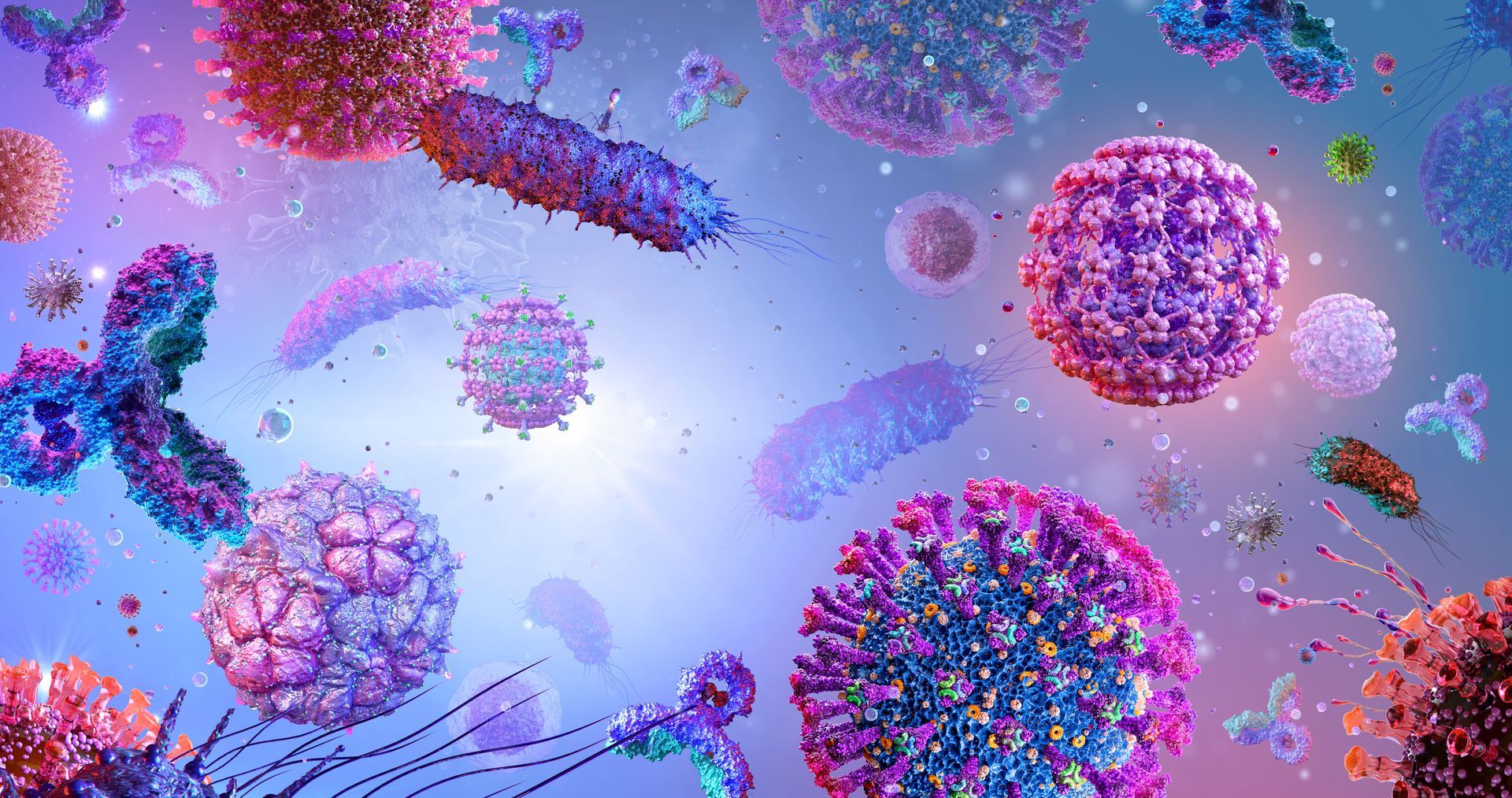

Any disease that circulates in animals, then passes to people, could cause a pandemic if it mutates to become either easier to catch, more deadly, or both. On the other hand it’s less transmissible than covid, and there are already vaccines and treatments.

The current Monkeypox genome has recently been sequenced. It looks like it’s ‘closely related’ to the same variant that turned up in the UK, Israel and Singapore in 2018 and then again in 2019. But nobody knows whether it’s a single variant running wild at the moment or more than one, nor do they know whether it has changed to make it more infectious. The reasons why it’s spreading so fast remain unknown, too.

Because the Monkeypox genome is a lot more complex than covid – with 200,000 or so RNA letters against covid’s 30,000 or so - it’ll take a while to figure things out. Scientists are carrying out more sequencing and analysis as we write.

Keep an eye on Monkeypox progress

Come back for the latest reliable news on the outbreak, fresh from the science community.