Covid has been terrible – But how about Bubonic Plague?

In 2021 the bacterium behind the Black Death turned up in a 5000 year old skull found in Latvia. It was the earliest ever plague strain discovered so far. And it served as a timely reminder: the next pandemic could be something new, or it could be something as ancient as the Black Death.

The black death plague remains, lurking under cover across the world, emerging now and again to cause havoc. While it’s very unlikely we’ll see another catastrophic event like the medieval plague, it’s worth remembering that despite all our modern vaccines and antibiotics, the disease still kills 10% of people who catch it. Covid’s 1% death rate looks harmless in comparison, and that managed to bring the entire world to a halt. No wonder experts are preparing for the worst.

Let’s take a look at the plague, how it affected the world in the past, and the risk it poses to the modern world.

A potted history of the plague

The infamous plague we all know about, which we’re taught about at school, kicked off in Crimea in 1347. By 1351 it had killed millions. The initial five year outbreak is thought to have killed half the population of medieval Europe. Then it died back. A few years later it returned for a second wave, killing over 50 million people before it subsided. This, the most famous outbreak of the black death, turned into a series of pandemics that went on killing people for five hundred years. But it wasn’t the first.

An earlier outbreak flattened Istanbul in AD 541, then spread around the world and kept going for over 200 years. There was another plague pandemic in 1772, this time in the Chinese province of Yunnan. It hit Hong Kong in 1894, spread via travellers, ended up killing about 20 million people, and finally ended during the 1940s. But, again, the bacterium that caused it survived. And in the USA, in 2015, 15 people caught it and 4 died, a mortality rate of over a quarter.

Plague remains common across the world

To this day, the plague breaks out and kills people. Yersinia pestis remains common in rats and other rodents, and in the parasites that live on their blood. The ‘zoonotic reservoirs’ it creates in wildlife are widespread, and there are many of them. This makes the plague impossible to completely get rid of. The only continent that’s free from it at the moment is Australia.

Just one man was responsible for the disease’s recent spread on the island of Madagascar. He infected dozens of passengers on the bus he was travelling on before dying in transit. By the time the outbreak had ended 202 people had died. India, China and the US have seen recent plague outbreaks, too. And now it’s being considered a ‘re-emerging disease’.

How come plague is making its way back?

The cause is humanity’s ‘relentless encroachment on nature’, which means we encounter animals carrying pathogens more frequently than ever before. The more we disturb land where people haven’t lived before, the closer contact we have with dangerous zoonotic reservoirs.

What happens when you catch bubonic plague?

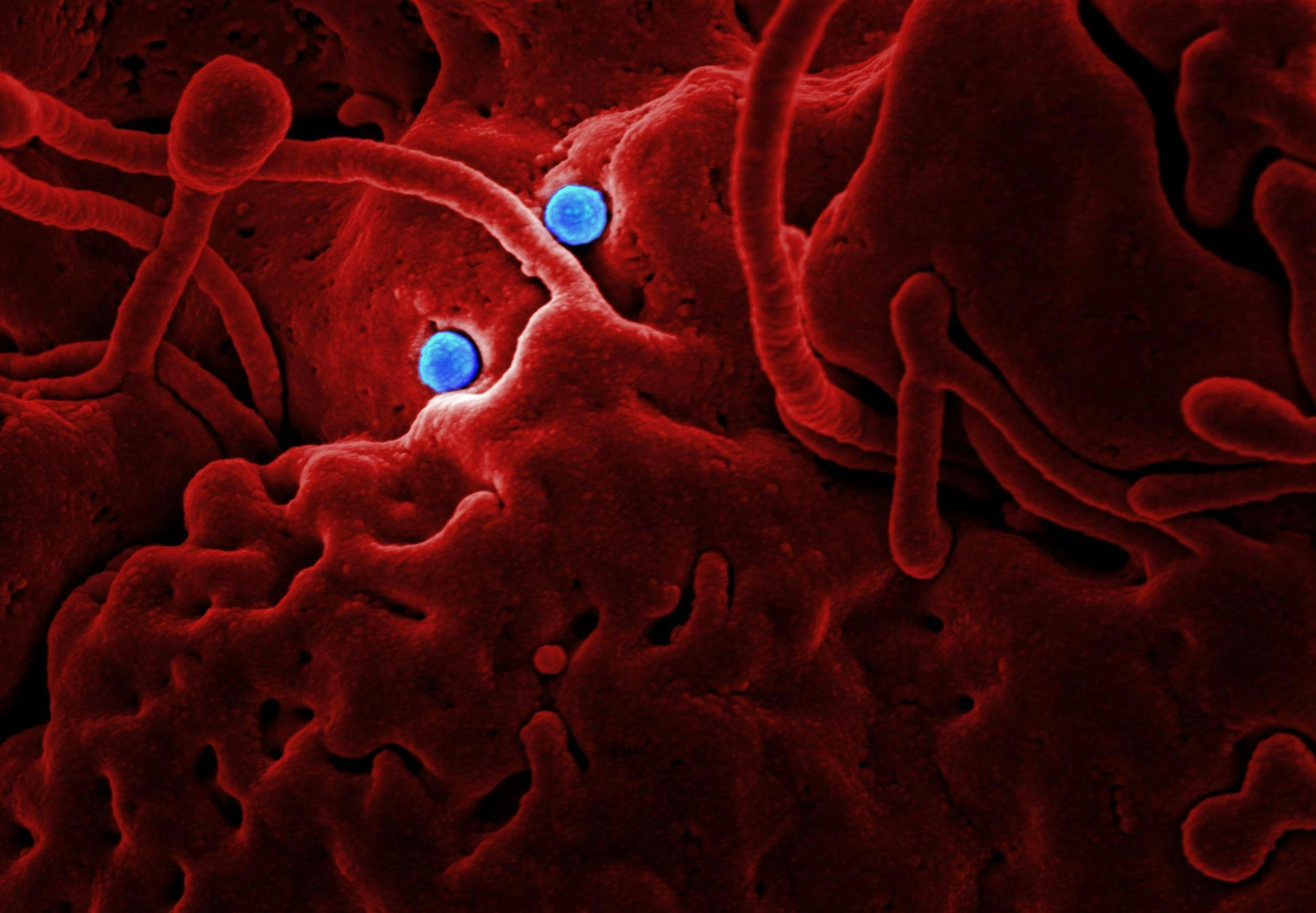

The bacterium invades the lymph nodes in the groin, armpit or neck then replicates incredibly fast, causing painful swellings called buboes. As little as two days later you get a sudden and violent attack of fever, chills, headaches, body aches, weakness, nausea, and vomiting.

If it gets into your blood it can turn into septicaemic plague. If it enters the lungs you end up with pneumonic plague. Septicaemic plague leads to actual septicaemia. Pneumonic plague morphs into pneumonia. Both almost always end in death. If you don’t get treatment, all varieties of the plague are ‘highly lethal’. If you’re lucky and your case doesn’t go pneumonic or septicaemic, your survival rate might be as high as 70%.

Outbreaks spread incredibly fast simply because the septicaemic version ends up back in parasites, and the pneumonic version spreads between people via infected respiratory droplets in the air or on surfaces, like covid.

Can the three types of plague be cured with antibiotics?

The plague can be cured with antibiotics. But the Madagascar outbreak we mentioned had a death rate of just under 10% despite a million doses of antibiotics being used to try to stop it. Most cases were pneumonic, which is only treatable during a small window of time, within 24 hours of symptoms appearing. If not, the fatality rate is almost 100%.

What about antibiotic resistance?

Antibiotic resistance would be horrific, making the best treatments we have useless. In fact it’s already happening. Scientists have found antibiotic resistance to ‘every drug recommended for treatment’ in samples from wild animals and infected people. Most remain treatable but if a strong drug-resistant strain turns up, it could ‘potentially be grim’.

What’s the best way to keep humanity safe from plague?

The best option, by far, is vaccination. The problem is existing plague vaccines are old, so old that the WHO can’t recommend them any more. While they’ve probably saved tens of millions of lives and helped to bring the plague pandemic to a halt over the years, they only provide short-lived immunity. And they don’t work at all against pneumonic plague.

There’s more. Some vaccines, called attenuated vaccines, come with a risk of serious side effects. Worse still, they could force the plague to morph back into its most dangerous form. While we’ve been lucky so far, a Chicago scientist died of an attenuated strain of the plague in 2009. His medical condition made the disease worse, but the genetic condition he had is common enough in ‘white people’ to make attenuated vaccines far too risky.

There are at least 20 new plague vaccines being worked on as we write. None of them, so far, have met the WHO criteria for a successful vaccine. Progress is slow. Funds and resources are limited. So let’s hope the plague doesn’t kick off again before an effective vaccine has been created, tested, and brought to market.

In the meantime, stay safe from a host of horrible pathogens with our UVC lights

Our affordable, convenient UCV light technology kills covid plus numerous other bacterial and viral diseases quickly and efficiently.