The Science Bit

Covid-19 T-cells, Antibodies and Immunity

There have been reports about more people being immune to the virus than scientists originally thought. Like all reports in the media, it's wise to take stories like this with a pinch of salt. We decided to check things out via our favourite science website, New Scientist, to see if they could help us find the truth. As it turns out, they can. Here's what you need to know about the fierce debates taking place around antibodies, T-cells, and the science of immunity.

Have we been ignoring T-cells for too long?

The latest scientific debate – which is actually more of a heated row – concerns whether we've been neglecting a vital element of the human immune response to the virus, namely the sterling work done by T-cells. It's important because better natural immunity to the virus could mean some of the stricter countermeasures we're taking as a society against Covid-19 might be unnecessary.

Fighting the virus with our antibodies

Apparently the human immune system features two main ways to fight off diseases like the coronavirus. The one we've all heard of is antibodies, little molecules that recognise specific pathogens and target them so our immune system can kill them. Antibodies are in our blood, easy to spot and widely used to pin down the proportion of people who have been infected.

Antibody levels are nowhere near high enough to provide us with herd immunity, which can only happen when so many people are immune to the virus – or are vulnerable to have died of it - that it can't spread any more. The figure for herd immunity is around 65% of the population. If we just 'let it happen', scientists reckon many hundreds of thousands of us will die before herd immunity is achieved, and a death rate like that is unacceptable.

London is a good example of where we were at a few weeks ago. Antibody levels in the capital stood at roughly 10% from 26th April to 9th August, and for most of the UK and Europe the number was also in single digits. It's clear we can't rely on herd immunity as a tactic, and some experts have even called the idea 'scientifically illiterate'.

So far there are hints that the worse you suffer from the virus, the better and longer your own antibody response is. If you are very ill you're immune for longer. If you don't get many symptoms, or you're symptomless, your natural antibody response doesn't last anywhere near as long. It looks like being immune doesn't mean you'll be immune forever, which makes the disease more like the common cold and flu than measles, where immunity means immunity.

The role of T-cells

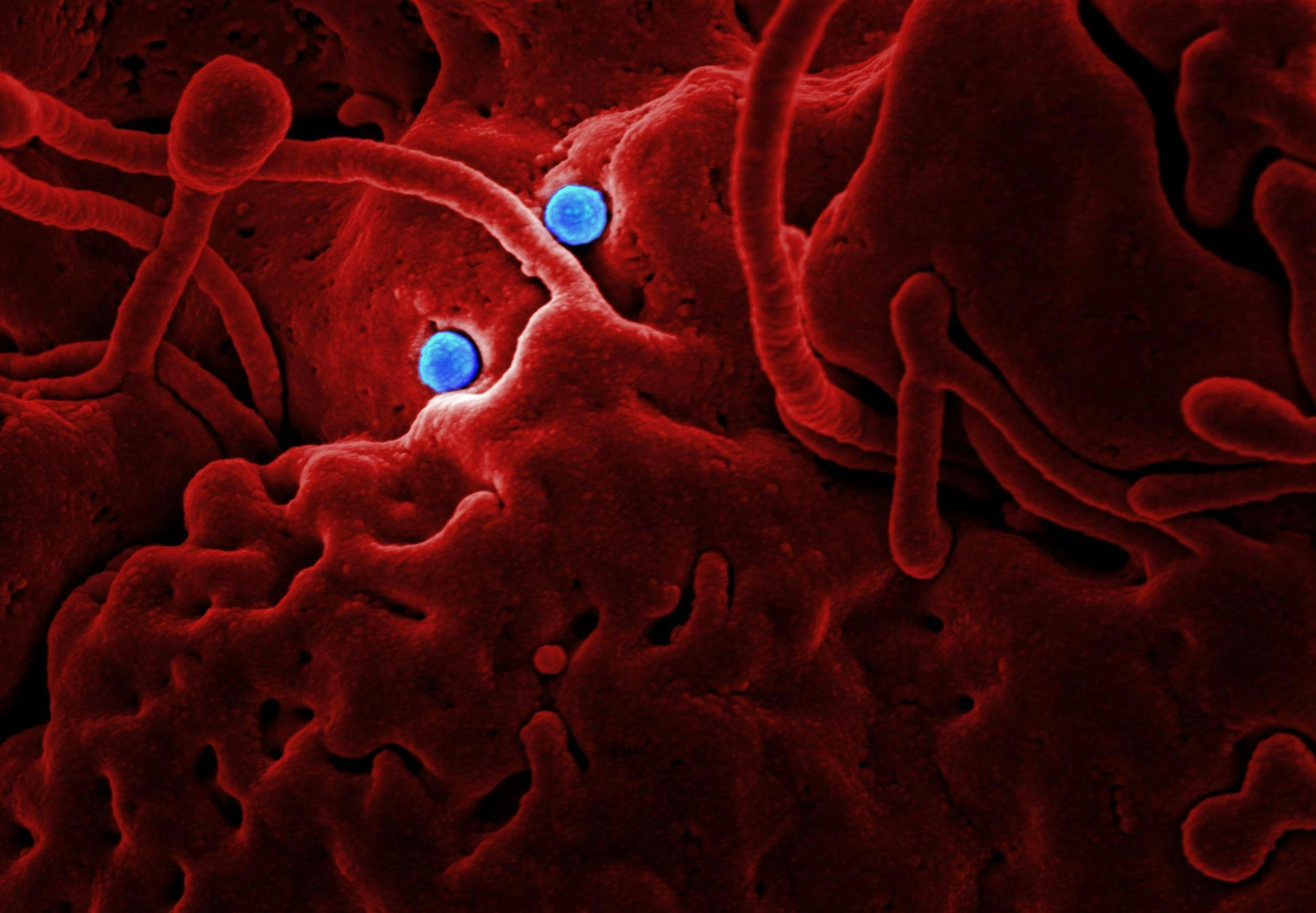

Once the virus is inside your body, T-cells are the only weapon you have to fight it. So far, small-scale studies have shown how T-cells react to the coronavirus in anything between 10% - 50% of people who have been tested. But that doesn't mean 10-50% of the population is immune. It looks like the pre-pandemic blood samples that tested positive were from people who had caught milder coronaviruses before, things like the common cold. The conclusion? It may be the case that these people won't get quite as ill with Covid-19, but they can still catch it and pass it on.

On the other hand one piece of Swedish research into 200 people - including some who'd already caught Covid-19 and their families - discovered the people who had been the most ill with the virus showed more T-cell activity. This suggests the T-cells' response was acting against Covid-19, not just an old incident of cold or flu. Like all scientists, though, the team is being careful about its claims: they can't confirm that every T-cell was induced by the new virus, so things remain mostly up in the air.

How long might T-cell immunity last?

We don't yet know how long antibody immunity will last. We also don't know long T-cell immunity will last. We've seen patients with confirmed Covid whose antibody tests are negative, but whose T-cells tested positive. It could be that antibodies are only part of the picture. One UK study shows a number of people whose partners had tested positive for the virus testing positive for T-cell activity, but they managed to avoid catching the virus themselves. Maybe the T-cells kept the virus at bay, but we just don't know. And until T-cell testing ramps up, we won't know.

The conclusion? As far as T-cells go, we can take these early findings as a cause for hope, “but not complacency.”

Get powerful UVC lighting units to keep your employees and customers safe

If you'd like to keep your customers safe, UVC lighting is excellent at disinfecting spaces quickly and efficiently.