About the latest mpox outbreak

About the latest mpox outbreak

For decades mpox stayed at home in Central and West Africa. Most Clade 1 cases came from Central Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo, with almost all Clade 2 cases, the less-serious version of the disease, found in Nigeria.

In 2022 the Clade 2 virus started spreading across Europe and North America. We had a WHO Clade 2 mpox warning in July 2022, which lasted to May 2023. Now Sweden has confirmed one case of the more dangerous Clade 1 version of the viral infection, just one day after the WHO declared it a global public health emergency. Apparently the person who caught it had spent time in an area of Africa where a lot of people had caught it, and this is the first case ever diagnosed outside Africa.

At the moment ‘Clade Ib’ is spreading fast in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and has already reached four African countries that have never been affected by the virus before. Overall mpox cases have been reported in at least 13 African countries. WHO boss Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus says the risk of it spreading out of Africa to other continents is “very worrying.” Other experts say the Africa outbreak is probably just the tip of the iceberg because we don’t yet have the full picture. As you can imagine, the world is watching.

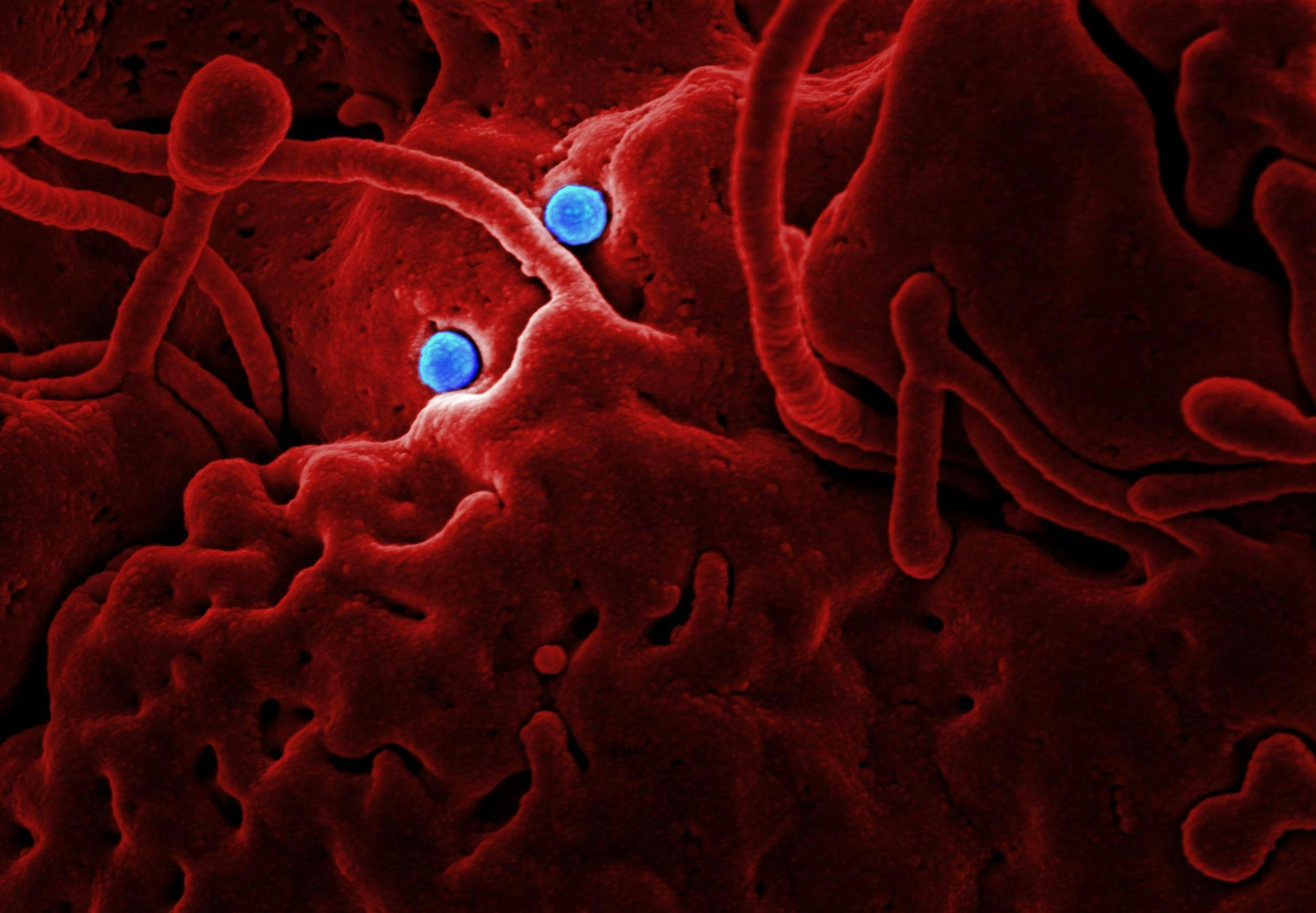

About mpox infection

The Mpox virus, AKA monkeypox, is related to the extinct smallpox virus. The disease spreads via close physical contact but can also spread through contaminated bed sheets, clothes and needles.

At first it feels a lot like flu, with a fever, tiredness, chills, headaches and weak muscles. Then a painful or itchy rash turns up, which inflames then forms scabs that take weeks to die down.

Clade 1 causes a more serious form of the disease. The subtype causing concern at the moment is called Clade 1b, which is relatively new, a mutation that has adapted itself to be more easily transmitted by humans and create bigger outbreaks.

Because we’re currently seeing multiple overlapping outbreaks of different Clades in various countries, each with slightly different transmission and level of seriousness, things are very uncertain.

Some outbreaks of Clade 1 mpox have killed as many as 10% of people who catch it. Several recent outbreaks have come with the lower death rates associated with Clade 2 disease, 0.2% or so. But some people, including babies and small children, pregnant women and those with badly weakened immune systems, are more likely to suffer from a serious infection from either Clade.

What do we know about mpox spreading?

One of the biggest issues is the resources needed to diagnose and treat mpox, which are spread far too thin in Africa for comfort. Even taking a simple sample in a remote rural area and sending it to a lab is a real challenge. This, and the fact that only the most severe cases might be detected, makes it hard to know what’s happening now and even harder to predict what happens next.

This time around the geographic pattern of outbreak is different from 2022-23. It’s reaching more countries than before, even though the vast majority of cases are being found in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

International travel is once more under the spotlight, and the old saying we all became so familiar with during covid is resurfacing: nobody is safe until everybody is safe. There are worries that because it’s mostly in Africa at the moment, rich western nations might not take the threat seriously enough or care enough about stamping it out before it’s too late.

Is there an mpox vaccine?

There’s a vaccine for mpox but it isn’t easily accessible in Africa. Experts say people in the USA at risk of catching it need to get vaccinated just in case. In the meantime the Vaccine Alliance has a maximum of $500 million to spend on sending mpox vaccines to the African countries affected by the current outbreak - but they’re not due to start stockpiling a global vaccine supply until 2026.

The WHO says vaccines are only the tip of the iceberg anyway. We’ll also need more surveillance, more diagnostics and more knowledge about the virus itself, which currently comes with ‘gaps in understanding.’ The WHO itself has half a million doses of vaccine in stock, with potential for another 2.4 million doses to be made by the end of 2024, and Nigeria and the DRC are first in the queue.

Can UVC light kill the mpox virus?

There’s no scientific reason why UVC sanitising tech can’t kill the mpox virus, in exactly the same way as it

kills a long list of other viruses – including covid, flu and the common cold – as well as dangerous bacteria, moulds, spores, protozoa and yeasts.

If you’d like to protect your employees, suppliers, partners, visitors, guests and customers from infections, illnesses and diseases, and keep your business open while others are forced to close, let’s talk about how our UVC light units can help. They’re widely used in numerous settings, including healthcare, and they form a vital line of defence.