Clean air special - Covid, ventilation, and UVC disinfection technology

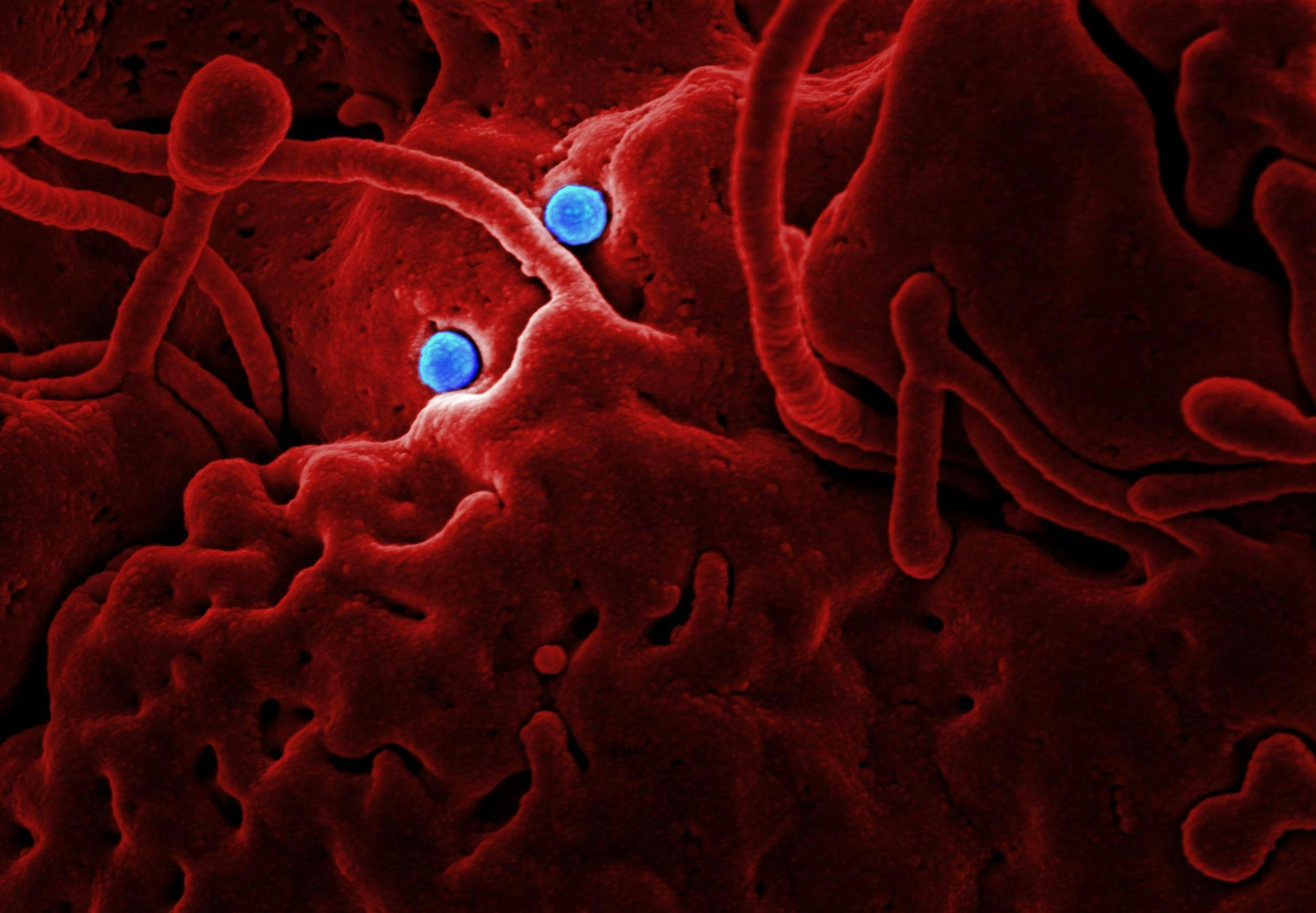

Scientists are calling it ‘the ventilation problem’. As winter approaches and the schools go back, it’s vital to improve the airflow in public spaces to reduce covid transmission. But there are big questions around the best technology to use, and even bigger questions around the tricky issue of retro-fitting suitable ventilation tech to thousands and thousands of buildings.

SAGE member Cath Noakes, an environmental engineer, says it all. In her words,

“Ventilation is a critically important control measure for covid-19.”

The WHO accepts airborne transmission is ‘critically important’.

Add the fact that schools are rarely ventilated well but are packed with mostly-unvaccinated children who are naturally not very good at social distancing, and the risk becomes even greater. Ultimately the same goes for all the spaces where people congregate, including workplaces, pubs and restaurants, colleges, gyms, cinemas and theatres, public loos, churches, and public transport.

It’s widely known covid is easily transported across a room in very small particles, and can quickly build up if there isn’t enough ventilation. We also know poor ventilation is a superspreader. But sadly ventilation isn’t as simple as opening a window.

How is good ventilation defined?

What, exactly, is ‘good’ ventilation? It’s another question we can’t answer. Some use a measure involving how many times the air is completely replaced per hour, but at the same time there’s no way to use that number to figure out the right ventilation rates in a buildings and manage covid infections. Add the fact that every building is different and it’s clear we’re in a difficult position. As Stephen Reicher from the University of St Andrews said,

“It’s all very well the government advising everyone to ‘ventilate’, but how can you know if public spaces aren’t well-ventilated if we don’t have clear standards, if those standards are not publicised and if the spaces are not monitored?”

A simple way to pin down the ventilation rate

Luckily you can use a CO2 monitor to estimate the amount of exhaled air in a space. The level of CO2 simply reveals how much of the air has been breathed out by other people, making it a handy little tool in the search of a reliable ventilation rate.

While the way a building is managed can also have a dramatic impact, ventilation tends to be low on the priority list because it’s hard to get right as well as invisible, seen as an expensive luxury rather than essential. Even if a building has a decent ventilation system it’s unlikely to be well maintained. Here in the UK only a tiny number of buildings have good ventilation built in. And many office building windows are not open-able for safety reasons.

Is air conditioning a good idea in a covid world?

Perhaps counter-intuitively, air conditioning can make things worse. Aircon as part of a wider mechanical ventilation system is usually OK. It cools the air while bringing in fresh air. But the most common systems, called recirculating units, just circulate the same air over and over.

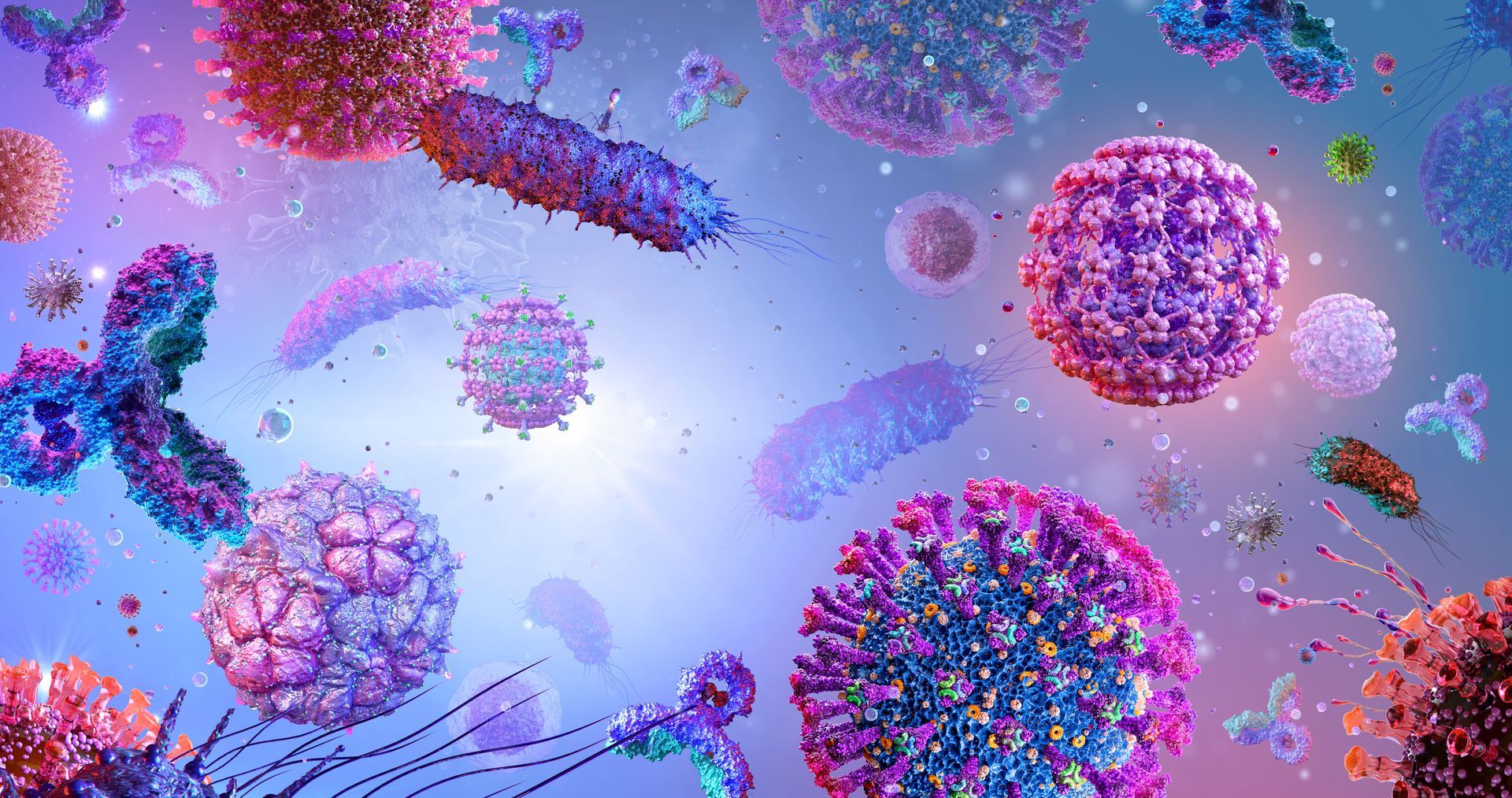

Filters could be useful. HEPA filters, AKA high-efficiency particulate absorbing filters, work well in some types of space but not all. In every case the tech needs to be designed to suit the specific environment. At the moment 30 Bradford primary schools are testing HEPA filters as well as UV light to see how they cut covid transmission. It’ll be interesting to see the results.

It’s important to understand that even the best-in-breed air cleaning system alone can’t keep us safe. Because ventilation only prevents airborne transmission beyond 1.5m from a person, we still need masks, distancing, surface cleaning, and strict hand-hygiene.

Poor air quality has bedevilled us for long enough

May saw an international team of researchers publishing an appeal for a ‘fundamental rethink’ about air quality. It has been a long time coming. They say today’s terrible indoor air quality fails to protect us from airborne pathogens like covid, and ‘must be upgraded’. They also say the challenge is as big as that faced by cities in the 1800s, when there was a deadly public health problem thanks to poor quality water and non-existent sewage systems.

Who is acting early?

New York City is publishing the air quality for every classroom in its public school system. They say every classroom must have at least two methods of ventilation. Belgium has started insisting that every public building displays its CO2 level. But in the UK we’re dragging our heels.

Let’s leave the last word to the scientists. Gabriel Scally, the president of the Royal Society of Medicine’s Epidemiology & Public Health Section: “This is an airborne disease. If it was coming through our water supply we’d take action, and we should be taking action with our air supplies.

Stephen Reicher from the University of St Andrews agrees. As he says,

“We wouldn’t tolerate our children having to drink water which infects them, but we seem to tolerate dirty air. There’s got to be a fundamental change in attitude.”

UVC LED covid disinfection helps fill the gap

Until every relevant UK building has the air quality the people who live and work in it deserve, there’s another reliable way to kill covid in the air and on surfaces, and it’s UVC tech. Used in healthcare settings for decades, we’ve used UVC technology to create brilliant UVC covid disinfection machines. They’re safe to use and the results are excellent. If you’d like to take steps to keep people safer, let’s explore the potential together.